The Religious Society of Friends, also referred to as the Quaker Movement, was founded in England in the 17th century by George Fox. He and other early Quakers, or Friends, were persecuted for their beliefs, which included the idea that the presence of God exists in every person. Quakers rejected elaborate religious ceremonies, didn’t have official clergy and believed in spiritual equality for men and women. Quaker missionaries first arrived in America in the mid-1650s. Quakers, who practice pacifism, played a key role in both the abolitionist and women’s rights movements.

In the 1640s, George Fox, then a young man and the son of a weaver, left his home in the English Midlands and traveled around the country on a spiritual quest. It was a time of religious turmoil in England, with people seeking reform in the Church of England or starting their own competing churches.

Over the course of his journey, as Fox met others searching for a more direct spiritual experience, he came to believe that the presence of God was found within people rather than in churches. He experienced what he referred to as “openings,” instances in which he felt God was talking directly to him.

Quaker Beliefs

Fox shared his religious beliefs and epiphanies with others, speaking to increasingly larger gatherings. Even though his views were viewed by some as a threat to society and he was jailed for blasphemy in 1650, Fox and other early Quakers continued to share their beliefs.

In 1652, he met Margaret Fell, who went on to become another leader in the early Quaker movement. Her home, Swarthmoor Hall in northwest England, served as a gathering place for many of the first Quakers. Fox and Fell married in 1667.

Meanwhile, “Quaker” emerged as a derisive nickname for Fox and others who shared his belief in the biblical passage that people should "tremble at the Word of the Lord." The group eventually embraced the term, although their official name became Religious Society of Friends. Members are referred to as Friends or Quakers.

What Is a Quaker?

Quakerism continued to spread across Britain during the 1650s, and by 1660 there were around 50,000 Quakers, according to some estimates.

A number of Quaker beliefs were considered radical, such as the idea that women and men were spiritual equals, and women could speak out during worship. Quakers didn’t have official ministers or religious rituals. They opted not to use honorific titles such as “Your Lordship” and “My Lady.”

Based on their interpretation of the Bible, Quakers were pacifists and refused to take legal oaths. Central to their beliefs was the idea that everyone had the Light of Christ within them.

Fox spent much of the 1660s behind bars, and by the 1680s thousands of Quakers across the British Isles had suffered decades of whippings, torture and imprisonment.

Colonial Quakers

Quaker missionaries arrived in North America in the mid-1650s. The first was Elizabeth Harris, who visited Virginia and Maryland. By the early 1660s, more than 50 other Quakers had followed Harris.

However, as they moved throughout the colonies, they continued to face persecution in certain places, particularly in Puritan-dominated Massachusetts, where several Quakers - later known as the Boston Martyrs - were executed during the 1650s and 1660s.

William Penn

In 1681, King Charles II gave William Penn, a wealthy English Quaker, a large land grant in America to pay off a debt owed to his family. Penn, who had been jailed multiple times for his Quaker beliefs, went on to found Pennsylvania as a sanctuary for religious freedom and tolerance.

Within just a few years, several thousand Friends had moved to Pennsylvania from Britain. Quakers were heavily involved in Pennsylvania’s new government and held positions of power in the first half of the 18th century, before deciding their political participation was forcing them to compromise some of their beliefs, including pacifism.

Quakers and Human Rights

The Quakers took up the cause of protecting Native Americans’ rights, creating schools and adoption centers. Relations between the two groups weren't always friendly, however, as many Quakers insisted upon Native American assimilation into Western culture.

Quakers were also early abolitionists. In 1758, Quakers in Philadelphia were ordered to stop buying and selling slaves. By the 1780s, all Quakers were barred from owning slaves.

Women's Suffrage Movement

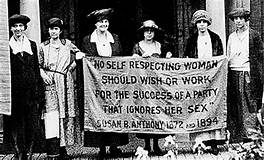

In the 19th century, many of the leaders of the women’s suffrage movement in the United States were Quakers, including Lucretia Mott and Alice Paul.

The women’s suffrage movement was a decades-long fight to win the right to vote for women in the United States. It took activists and reformers nearly 100 years to win that right, and the campaign was not easy: Disagreements over strategy threatened to cripple the movement more than once. But on August 18, 1920, the 19th Amendment to the Constitution was finally ratified, enfranchising all American women and declaring for the first time that they, like men, deserve all the rights and responsibilities of citizenship.

* Source: https://www.history.com/topics/womens-history/the-fight-for-womens-suffrage

One of the often unsung heros of this movement is Alice Paul.

Alice was raised in a Quaker home in Paulsboro (near Moorestown, NJ). Born in 1885, Alice studied at Swarthmore...

For more information, watch this video of Mary Walton speak about Alice Paul and Mary's book "A Women's Crusade: Alice Paul and the Battle for the Ballot"

* More information about Quakers at

https://www.history.com/topics/immigration/history-of-quakerism